Options Trading Masterclass By Usman Ashraf

Options trading often looks complicated. Strike prices, expiration dates, premiums, calls, puts, and Greeks — it’s a lot to take in at once. But when broken down step by step, options reveal themselves as one of the most versatile and powerful tools available to traders.

This guide will walk you through the essential building blocks of options trading. By the end, you’ll understand how options work, why traders use them, and what makes them different from simply buying or selling shares.

What Is an Option?

An option is a financial contract linked to a stock (or another asset). It gives you the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell that stock at a specific price within a set time frame.

Each option contract represents 100 shares of the underlying stock. Instead of paying the full cost of owning those shares, you pay only a fraction — known as the premium.

For example:

- If AMD trades at $95, buying 100 shares costs $9,500.

- An option contract might cost just $50.

- That $50 premium gives you control of 100 shares, with your maximum risk capped at the premium itself.

This leverage is what makes options so attractive: they allow you to control a large position with far less capital.

The Three Core Parts of an Option

Every option contract is built on three key elements:

- Expiration Date: The contract only lasts for a set time (days, weeks, or months). If the stock doesn’t move in your favor before expiration, the option can expire worthless.

- Strike Price: The price at which you can buy (for a call) or sell (for a put) the stock.

- Premium: The price you pay for the contract. This is also the maximum risk for the buyer.

Understanding these three components is the first step toward making sense of how options work.

A House Example

Think of options like putting down a deposit on a house. Suppose a home is worth $200,000. Instead of paying the full amount upfront, you pay $1,000 for a contract giving you the right to buy it at that price within one month.

Two scenarios might play out:

- If the value falls to $150,000, you walk away. Your loss is limited to the $1,000 deposit.

- If the value rises to $300,000, you can still purchase it for $200,000 and resell it immediately for $100,000 profit.

This example mirrors an option: the deposit is the premium, the home price is the strike, and the one-month window is the expiration. The downside is limited, but the upside can be significant

A Car Example

The same idea works with a car. Imagine a vehicle priced at $50,000. Instead of paying the full amount upfront, you put down a $500 deposit that secures the car for three weeks.

If the car’s value doesn’t change, your only loss is the $500 deposit. But if the value rises to $70,000 during that period, you still have the right to buy it for $50,000. You could either purchase the car at the lower price or sell your contract to someone else for a profit.

This example captures the essence of options trading: your downside is limited to the deposit, while your upside can be much greater.

Buyers and Sellers

Every option has two sides:

- Buyers pay the premium for the right to exercise the contract. Their risk is capped at that premium.

- Sellers (or writers) collect the premium but carry far greater risk if the trade moves against them.

For beginners, buying options is usually safer and simpler, since the risk is clearly defined.

Calls and Puts

Options come in two forms: calls and puts.

- Call options give the buyer the right to purchase a stock at the strike price before expiration. Traders buy calls when they expect the stock to rise.

- Put options give the buyer the right to sell a stock at the strike price before expiration. Traders buy puts when they expect the stock to fall.

The buyer of a call profits if the stock price moves higher, while the seller of that call benefits if the price stays the same or drops. On the other hand, the buyer of a put profits if the stock price falls, while the seller of the put gains if the price holds steady or moves up.

This constant push and pull between buyers and sellers is what drives the entire options market.

Exercising vs. Trading the Premium

While options technically allow you to buy or sell the underlying shares, most traders never exercise them. Instead, they trade the premium itself. For example:

- AMD trades at $95.

- You buy a call with a $97 strike for $0.50 ($50 per contract).

- If AMD rises to $98, the premium might increase to $1.50.

- You sell the option for $150, tripling your money — without ever buying the shares.

For most retail traders, trading the premium is more practical than exercising the option.

In the Money, At the Money, and Out of the Money

Options are often described in terms of where the strike price sits relative to the current stock price.

- In the Money (ITM): The option already has value if exercised. For example, a call option with a strike price below the current stock price is in the money.

- At the Money (ATM): The strike price is very close to the stock’s current price.

- Out of the Money (OTM): The strike price is further away from the current price. These contracts are cheaper but riskier, since the stock must make a significant move before they become profitable.

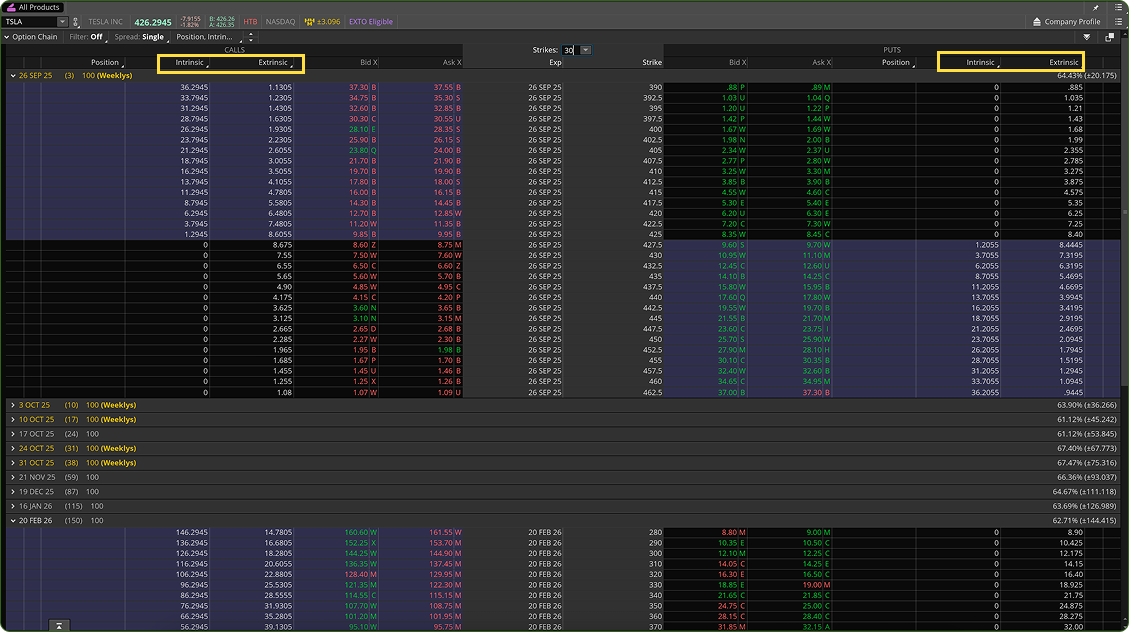

Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Value

An option’s premium is made up of two parts:

- Intrinsic Value: The actual, built-in value if the contract were exercised immediately.

- Extrinsic Value (Time Value): The additional cost based on the time remaining until expiration and the market’s expectations of future movement.

As expiration approaches, the extrinsic value steadily decreases. This process, known as time decay, is one of the most important dynamics in options trading.

Why Time Matters

Unlike shares, which can be held indefinitely, options contracts come with an expiration date. This means they are constantly losing value as time passes. Even if the stock price stays the same, the option’s premium erodes day by day because of time decay. By the time expiration arrives, all that remains is the intrinsic value, if any.

This makes options unique: you aren’t just trading the direction of the market — you are trading direction within a limited amount of time.

Implied Volatility (IV)

One of the biggest factors that influences the price of an option is implied volatility (IV). IV reflects the market’s expectation of how much the stock might move in the future.

When implied volatility rises, option premiums become more expensive because traders expect larger price swings. When IV falls, options become cheaper since the market anticipates smaller moves.

For example, before a company announces earnings, implied volatility usually spikes because traders expect a big move in the stock. Once the news is released, IV often drops sharply, and option prices fall with it. This is known as volatility crush.

Understanding IV is crucial because it explains why two options with the same strike and expiration can have very different prices at different times.

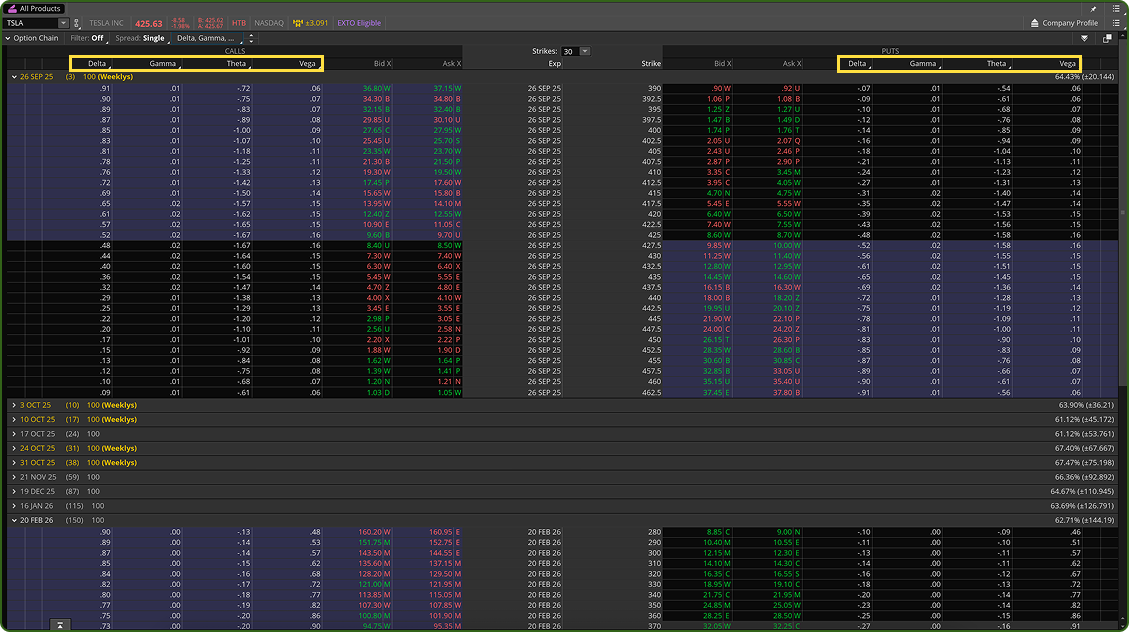

The Greeks: Measuring Risk and Change

Option prices don’t just move with the stock — they react to time, volatility, and probability. To make sense of this, traders use a set of measurements called the Greeks. Each Greek describes how sensitive an option is to a different factor.

Delta

Delta measures how much an option’s price will change for every $1 move in the underlying stock.

- A delta of 0.50 means the option will gain or lose about $0.50 for each $1 move in the stock.

- Calls have positive deltas (they gain value as the stock rises), while puts have negative deltas (they gain as the stock falls).

Gamma

Gamma measures how quickly delta changes as the stock moves. High gamma means delta can shift rapidly, which often happens in options with little time left. Gamma is especially important for short-term and zero-day options, where price swings can be sharp.

Theta

Theta represents time decay, how much value an option loses each day if everything else stays the same.

- If an option has a theta of –0.10, it will lose $0.10 in value every day until expiration.

- This is why buying options too close to expiration can be risky: time is constantly working against the buyer.

Vega

Vega measures how much an option’s price will change with a 1% change in implied volatility. If vega is 0.20, a 1% rise in volatility adds $0.20 to the option’s premium.

Why the Greeks Matter

Together, the Greeks give traders a complete picture of how an option behaves:

- Delta tells you how much the option moves with the stock.

- Gamma shows how fast that relationship changes.

- Theta reveals how time decay erodes value.

- Vega explains how volatility impacts pricing.

By tracking these numbers, traders can manage risk, understand potential outcomes, and make smarter decisions about which contracts to trade.

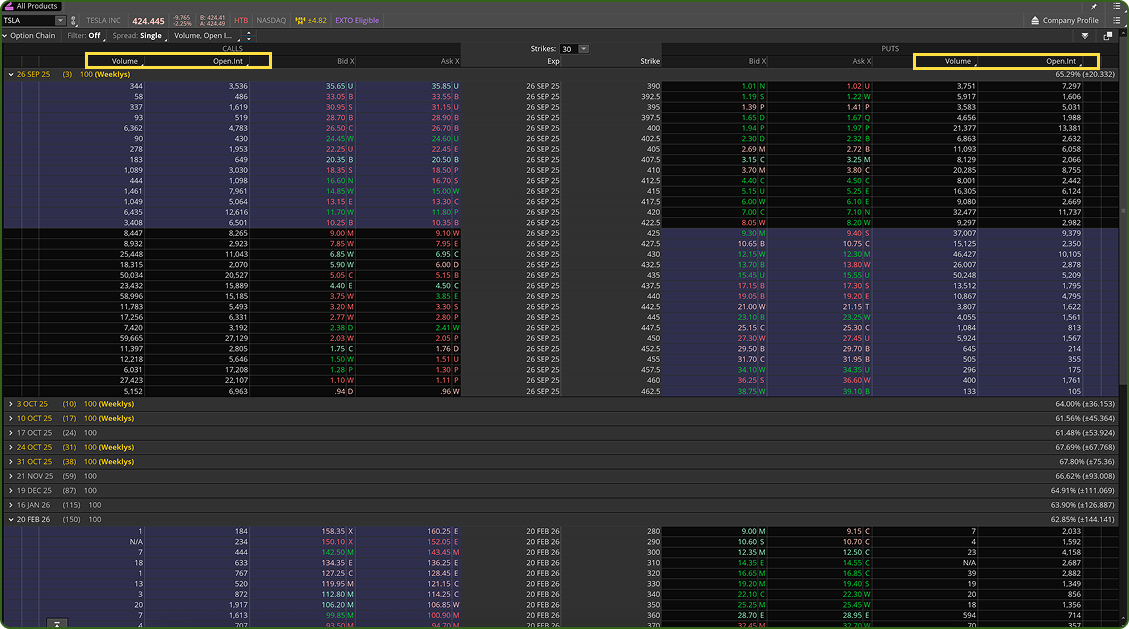

Liquidity: Volume and Open Interest

When choosing an option, price isn’t the only factor — liquidity matters just as much. Liquidity determines how easily you can get in and out of a trade without delays or poor fills.

Two key measures are:

- Volume: How many contracts have been traded during the current session. This resets to zero at the market open each day.

- Open Interest (OI): The total number of outstanding contracts that remain open from previous sessions.

High open interest means more market participants at that strike, which generally leads to smoother and faster fills.

For example, if a strike only has 100 contracts of open interest and you want to buy 70 contracts, you may struggle to get filled quickly. By contrast, if OI is 10,000, you’ll have no problem entering or exiting.

In short: volume shows today’s activity, while open interest shows the bigger picture of how many contracts are actually open in the market.

Position Sizing and Risk

One of the biggest hurdles for new traders is handling risk. In options, the maximum risk for a buyer is always the premium paid. But how you size your positions matters.

- Short-term options (like weekly or zero-day contracts) can produce explosive gains but also decay quickly. A small sideways move can wipe out much of the premium.

- Longer-term options (monthly or LEAPS) move more slowly but provide a cushion against time decay.

The key is matching your position size and expiration to your trading style. Day traders may prefer weekly or zero-day contracts, while swing traders often benefit from expirations weeks or months away.

Some traders treat the entire premium paid as their risk (“sizing to zero”). Others prefer stop-losses based on premium value or price levels. Both approaches can work, but risk management is essential. Options offer incredible leverage — but without discipline, losses can compound just as quickly as gains.

Key Takeaways

Options may look complex, but at their core, they’re simple: contracts built on strike, expiration, and premium. What makes them powerful is how time, volatility, and the Greeks shape their value. With the right strike, expiration, and risk management, options give traders flexibility and leverage that shares alone cannot.

Master the basics, respect the risks, and options can become one of the most effective tools in your trading arsenal.

.svg)

.svg)